Following Footsteps

Years ago we traveled as a family to Boston in the heat of August. We were all drenched in sweat as we walked into the cool air-conditioning of the National Park Service building outside of the USS Constitution.

Our daughter Kyle, 11, wiped her brow and announced quite loudly, “I hate history!”

The woman behind the counter shined a big, bright smile at Kyle and said, “Honey, if it weren’t for history, you wouldn’t be here!”

Ever since that exchange, I think about those who walked in the paths I’ve traveled. I think about their lives and their families. And in the case of our first stop on our historical tour through Alabama and Mississippi, I think about how they fought and died for what they believed to be true.

Vicksburg National Military Park

Vicksburg sits on the edge of the great Mississippi River. The city stood at the crossroads of the Civil War. The Union troops, led by Ulysses S. Grant, were on a mission to lay siege to Vicksburg and command control of the Mississippi. The Confederate soldiers reported to John C. Pemberton as they attempted to defend this strategic stronghold.

President Abraham Lincoln said, “Vicksburg is the key…the war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket. Confederate President Jefferson Davis stated that Vicksburg was “the nailhead that holds the South’s two halves together.”

For 47 days beginning in May of 1863, the 33,000 Confederate soldiers and 77,000 Union soldiers fought valiantly over that “nailhead” and key. The Confederates built fortifications and rifle pits out of the rich soil. They dug in deep ravines as they fought off the multiple assaults and bombardment of continual cannon fire from the Union troops.

Photo credit: Vicksburg National Military Park

Ultimately, lack of food, supplies and sickness took its toll on the Confederates. Grant and Pemberton met to discuss terms of the Confederate surrender. Grant wanted unconditional terms, which Pemberton refused. Grant reconsidered overnight, and on July 4, the Confederate troops laid down their arms and walked away from the battlefield, their white flags of surrender waving in the hot summer air.

The estimated casualties were 37, 273. Each side lost roughly 800 soldiers to the battle, but more foretelling is that the Confederate troops counted 29,620 as missing or captured.

Art to Honor

The Vicksburg National Military Park was established in 1899, and soon after the country’s top monument architects and engineers were commissioned to create monuments dedicated to the soldiers who fought in the battle.

We marveled at the artistry and were moved by the powerful sentiments. Here are a few of the monuments that correspond with the battlefield positions of the Union and Confederate soldiers.

This is the memorial to the Wisconsin troops. A bronze statue of “Old Abe” the war eagle mascot of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry sits on top of the memorial. Bronze tablets on the statue reflect the names of the 9,075 Wisconsin troops who fought at Vicksburg.

The memorial to the Alabama men who fought features seven soldiers being inspired by a women, who is intended to represent the state itself. This magnificent work was sculpted by German artist Steffen Thomas, who emigrated to the United States and lived in Stone Mountain, Georgia. Here is a link to the museum which was created in his honor. I’ve never been…will have to check it out next time we visit Kyle in Atlanta.

The memorial to the Arkansas soldiers was created out of marble from Mount Airy, North Carolina. The inscription reads, “To the Arkansas Confederate Soldiers and Sailors, a part of a nation divided by the sword and reunited at the altar of faith.”

Unknown Soldiers and Dog Tags

The Vicksburg National Cemetery was established on the site in 1866. It is one of the first national cemeteries in the country and the largest Union cemetery. We discovered that of the 17,000 soldiers buried here, 13,000 of the identities are unknown.

To try and prevent being buried as an unknown soldier, some marked their clothing with pinned-on tags, or with stencils. Others used old coins or even carved their name on a piece of wood their carried. It wasn’t until after the Spanish-American War that official identification, i.e. “dog tags” were required to be worn by soldiers.

The Vicksburg National Cemetery. Photo Credit: NPS

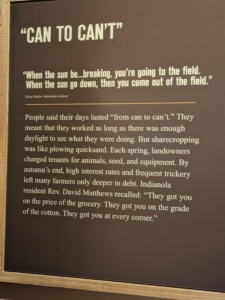

A young boy was born to sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta in 1925. His parents separated when he was five, and by the age of seven, he was out in the cotton fields working away. His mother died when he was just nine years old, and was sent to live with his grandmother, who passed away just five years later.

A young boy was born to sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta in 1925. His parents separated when he was five, and by the age of seven, he was out in the cotton fields working away. His mother died when he was just nine years old, and was sent to live with his grandmother, who passed away just five years later.

The boy, Riley King, befriended the guitar-playing minister at his grandmother’s church.

The rest is history.

Riley played on street corners on Saturday nights, and on Sunday mornings with the St. John’s Gospel Singers. Riley broke away from the group, hitchhiking to Memphis in 1947 to pursue a career in music.

Just a year later, Riley landed on the KWEM radio station out of West Memphis. Riley earned the nickname Beale Street Blues Boy, later shortened to simply B.B. King.

We spent several hours at the museum. learning about B.B. King’s journey from busking on streets to becoming an international icon. The thread of civil rights is woven through his story, and represented quite well throughout the exhibits.

My favorite story from his early days touring involved needing to stop for gas to fuel up “Big Red,” his first tour bus. When B.B. stepped out of the coach to use the restrooms, often the station owner sized B.B. up and told him the restrooms were closed. B.B. walked over to the bus driver and told him to stop pumping gas. No restrooms, no gas sale.

My favorite story from his early days touring involved needing to stop for gas to fuel up “Big Red,” his first tour bus. When B.B. stepped out of the coach to use the restrooms, often the station owner sized B.B. up and told him the restrooms were closed. B.B. walked over to the bus driver and told him to stop pumping gas. No restrooms, no gas sale.

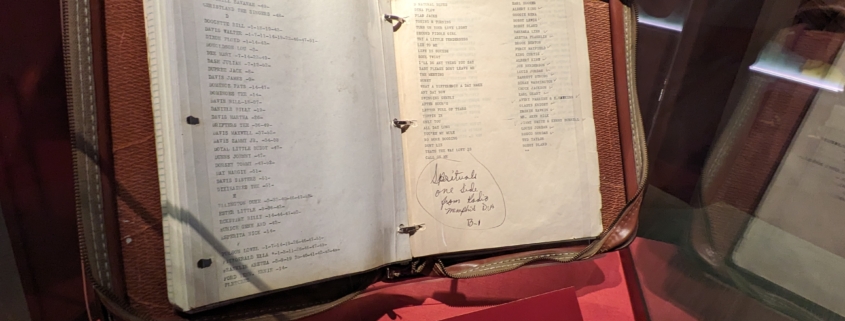

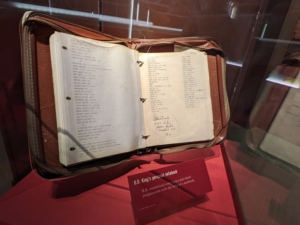

B.B. King’s personal journal.

Blues legend B.B. King passed away in 2015 at the age of 89.

Here’s a link to one of his top hits, “The Thrill is Gone.”

Southern Homes…from Plantation to Frank Lloyd Wright

Brad discovered the Belmont Plantation and the Frank Lloyd Wright Rosenbaum House during our travels.

We were transported back into the antebellum past in the Belmont, resplendent with all the trappings of a southern plantation. Then, we were jettisoned into the simplicity of a Usonian home with it’s simple L-shaped grid, flat roof and efficient use of space in the Rosenbaum home.

The Belmont was built between 1855-1861. It has 9,000 square feet.

The original Rosenbaum House was 1540 square feet and took just nine months to build.

Both Storied Histories

Dr. William Worthington, the original Belmont owner, was both planter and medicine man. He possessed over 80 slaves. According to the Belmont’s current owner, Bradley Hauser, the slaves were taught to read and write and well cared for. Bradley is currently researching the families who lived as slaves at the plantation.

When Stanley Rosenbaum married Mildred, a native New Yorker, Stanley’s parents were worried that the newlyweds would move to New York. So they gifted the young couple with the property right across the street from their home. Wright was commissioned to build the home for the Stanley and Mildred and was completed in 1939.

The Belmont Plantation and the Rosenbaum House. Photo credit: wrightinalabama.com

Major Restorations to Both

The Belmont Plantation has been through a number of restorations over the years. After a series of families owned the home, by 2014 the bank foreclosed on the property. The front porches were falling down, the plumbing system was a mess, the roof leaked, and worst of all, a number of Delta critters had taken residence in the once stately mansion. Joshua Cain bought the house in 2015 and restored the home to its original glory, including many of the Worthington’s furnishings.

The Belmont Plantation has been through a number of restorations over the years. After a series of families owned the home, by 2014 the bank foreclosed on the property. The front porches were falling down, the plumbing system was a mess, the roof leaked, and worst of all, a number of Delta critters had taken residence in the once stately mansion. Joshua Cain bought the house in 2015 and restored the home to its original glory, including many of the Worthington’s furnishings.

Bradley Hauser continues to preserve the home, which serves as a Bed & Breakfast.

The foyer (l.) and the women’s parlor at the Belmont.

The Rosenbaum home remained a family home until 1999, when Mildred passed away. She attempted to sell the house before she died. After she interviewed a prospective buyer, she refused, as he intended to make too many changes to the beloved Wright-designed home.

The City of Florence and Mildred ultimately came to an agreement for the municipality to purchase and preserve the home. An extensive restoration costing $750,000 began in 1999. Work included replacing the leaking roof, replacing termite damaged walls and updating the antiquated heating and air-conditioning systems.

Across the street from the home is a small museum (tickets for tours can be purchased here) and includes a number of photos of the home during the renovations.

The front living space and the dining room in the Rosenbaum House.

Footsteps.

From the rapid-fire chases in the ditches at Vicksburg, to those of B.B. King as he faced racism on tour. From the pained steps of slaves in the South, to the pitter patter of the Rosenbaum children in their unique home.

We can only begin to imagine their lives by following in their footsteps.

Some day the same will be said about ours.